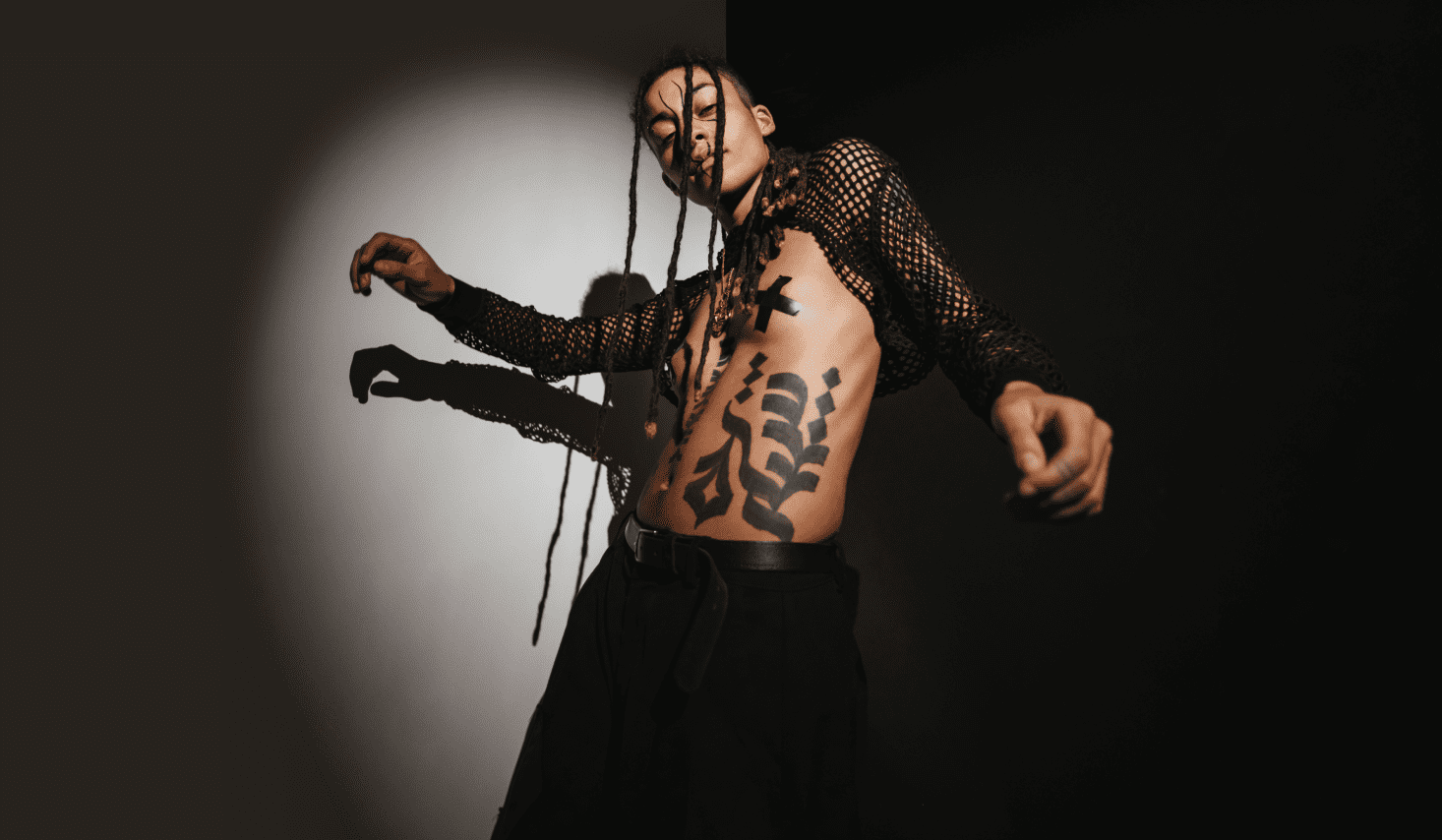

They’ve taken over the GAY TIMES stage at The Great Escape and made their name with straight-talking tracks, so if you don’t know who Grove is, well, you’re missing out. From unfiltered lyrics to potent, unpredictable dancehall-meets-rave tunes, there’s no one making moves like this Bristol breakout talent.

The artist’s debut release Queer + Black was a statement to their sound and, now, in their wave of new music, Grove is setting down a new record. Whether they’re to using music as a means to let off steam or call out the political injustices in the UK, Grove is guaranteed to carve up the scene and make their voice heard.

So, following on from their killer set on our stage, we caught up with Grove to hear more about their rise as an up-and-coming star and how the value of community inspires their sound.

Hey Grove! So, you’re a Bristol artist. What does the city mean to you?

I moved to Bristol about four years ago. The first year was this beautiful, expansive brain experience and really had a sense of community and belonging. Bristol’s got an interesting context now. For the past year and a half, housing prices and the way of living in Bristol is shifting. There are so many people who are without housing and there’s this collective sense of struggle.

But, realistically, with this struggle, there are a lot of people who are having to leave the place that they love which has been such a hub for them. So, it’s there’s this bittersweetness to it at the minute. It’s a struggle that means you can be together and get through, but it’s very divisive at the minute.

Outside of Bristol, where did you get your start in music?

My start in music came from the community. There was this community studio in Gloucestershire where I grew up. Essentially, it’s the work of one man called Malikai Patterson who wanted to give young people who weren’t making classical music, which is very well funded, he tools, the confidence and the skills to be able to do what I’m doing now.

[Patterson] put on these development programmes as well as running the studio. Before I came to Bristol, I was involved in this lovely, tight-knit supportive community studio environment that was like a charity. I didn’t have opportunities to learn these kinds of things in school so I was doing that for about four years before moving to Bristol.

With your own catalogue of music, you’re very hands-on with what you create and produce. How does that skill add to your music?

I first started making little demos eight years ago and then I started making them on a laptop a year after that. I initially wanted to make pop tunes. I wanted them to be pure pop with little sprinkles of dancehall but clean with weird sounds.

Growing up, I’d avoided acknowledging darker emotions and that’s not to say dark as evil, but dark as in the uncomfortable emotions that I had been experiencing my whole life. It enabled me so that I was able to create a whole soundscape. You could create this world that reflected the inner world. Some people are incredible with words and could do that with words but the combination of doing that with words and the sounds is where it feels most right for me.

The pillars of your music have centred around the sound and you’re very direct lyricism. Is that a method you’ve reliably used?

Very, very direct! It’s been something I’ve been wrestling with recently. I’ve been reading various books on music. Some people’s opinions are that the best kind of songs are the ones that are so nuanced and then you fill in the gaps. I think it’s a beautiful skill to have and there’s definitely a time and a place for that. But, when I write, I can’t dance around it. This is the thing that I’m thinking and I need to say it how in its raw worst form. it’s boom, splat on the canvas! It’s just what naturally comes to me.

You’ve got a couple of killer new singles out now. What’s the main motive behind each track?

‘Stinkin Rich Families’ is meant to make people angry. I think the worst thing that can happen is apathy. ‘Dead Bird Blues’ is more reflective, and aims to turn that universal sense of despair into something meaningful.

You’ve also released your anti-monarchy banger, ‘Big Boots’. How did that song come about?

I started making that track when Queen Elizabeth died. It naturally finished in the recent few weeks. It felt natural to get out in time for this new transfer of power. It’s a bizarre, confusing time, but it’s also filled with the same rage and reflection as when it was made.

[The title] came from the phrase “bootlicker”, the boot is the establishment and that is the power. It’s really interesting hearing your perspective in terms of the skinheads and that wasn’t a particular thing that I had considered but it was more subverting the illusion that the police boot the truncheon is the power. The real strength lies in the boots start on our fucking feet! The boots on our feet, that we are proud to wear, are much bigger than any other boots, so that was something I was aware of.

What can fans and listeners expect from this new project?

For this first half of the EP, expect a spicy sonic and lyrical playground. Abrasive mixed with slick, direct mixed with abstract. It’s definitely ‘harder’ to listen to vs. previous releases – but I hope it’s enjoyed nonetheless.

You’ve described your new EP, P*W*R, as the first half of a double EP. What messages are you trying to share about power in today’s world?

There are 4 different types of inter-relational power: power over, power with, power to, and power within. The most commonly understood is ‘power over’. That is the version of power that is warped, corrupt and a product of the excessive greed that is rewarded in the upper echelons of society.

True power is the most potent & beautiful thing and is a product of power with (solidarity), power to (mutual support) and power within (solid sense of self-worth). Those who exercise power often seek to erase and weaken solidarity, mutual support and self-worth since that is the only way their power is legitimised.

With previous projects, you’ve tapped into topics of queerness, Black identity and politics. How has P*W*R been different for you?

With Queer + Black, there was a lot of life experience that went into those first few tracks. I don’t write things really quickly. I really like to amass that life experience again and put that into really intentional and meaningful. slices of song and sonic stuff. In terms of my Blackness and my queerness, it’s not directly put into that, it’s more my observations of class and power structures. There’s plenty more coming out that explores the multitude of identities that I feel reside within.

You’ve also become part of a shifting image of alternative music that incorporates more variation of identity. What’s that experience been like?

It feels great. I’ve seen this hardcore band called Soul Glo in the UK recently and this other digital hardcore band called Horror and it’s this next level of catharsis that I experienced when listening in my headphones or live because there’s this deep sense of relation that I really didn’t feel a lot of in my life up until a few years ago. It’s grounding in many ways and makes the world feel a bit less lonely, which is always nice.

We’re all excited for what’s to come next. What can tell us about the second half of your double EP?

I’m thinking of the 2 EPs as 2 different flavours. P*W*R is the salty and the next one will be the sweet.