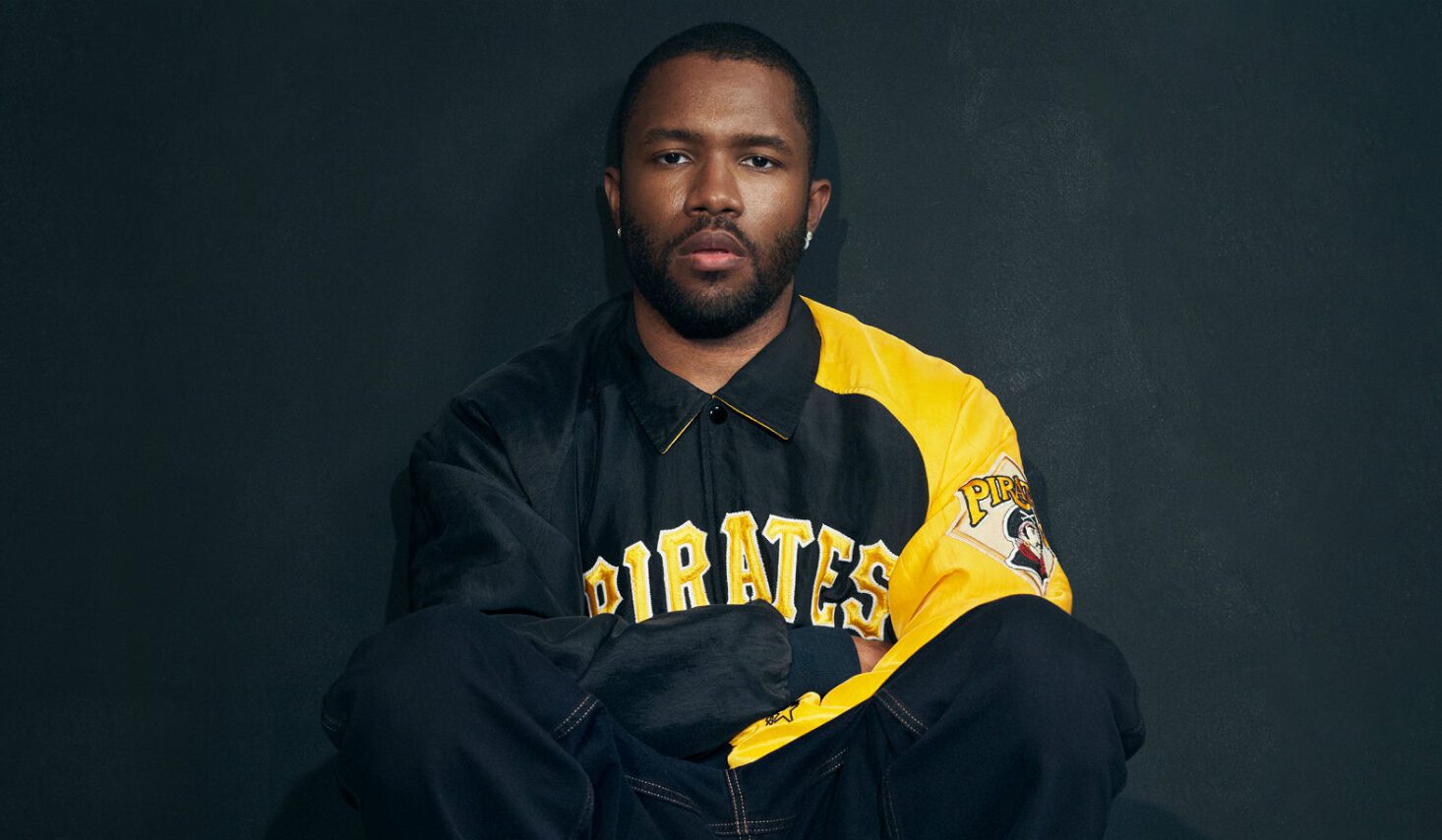

When I was eleven, and had no interest in social media, iTunes was where I devoted my screen time, dipping into as many different musical pools as I could afford to at such a young age. That summer, I was particularly drawn to the 50s, and, by chance, I came across an album called Channel Orange by Frank Ocean.

It seemed like a classic album, previewing a sonic landscape that referenced vintage television sets. I remember thinking, “Frank Ocean sounds like a name from the 50s”. Naively assuming that my parents would know of him, I bought the album and told them about it. They had no idea who he was.

What I didn’t realise is that I was accidentally buying a new R&B album that would change me forever – although, at that age, I would be yet to understand some of the adult references in the album’s lyrics, nor would I know that Frank had addressed his sexuality, something that I was yet to consider myself, in the same July during which the album dropped.

All I knew is that I liked his music – I listened to Fertilizer, a 40-second television skit, and Sweet Life, a vivid, neo-soul imagining and tearing apart of a wealthy summer, more than anything else at the time.

At first, my listening experience remained the same as I began to learn more about Frank (who is, to clarify, the coolest guy in the world), whether those details were of his sexuality or just how he lives his life. Channel Orange is more than a musical pool, each song a corner of the penthouse apartment built inside Frank’s mind.

In warmly lit rooms, it yearns for the night and then aches right through it. It holds up on its own.

Channel Orange didn’t need to be contextualised for me to appreciate it in 2012, but as I grew up, I grew fonder of the context, and it became clearer as to why this album had ended up in my hands. At 14 tracks in, Bad Religion pulls up and drives you away, speeding into the personal details of Frank’s unrequited love for another man.

This narrated a heavy part of my teenage years, and I found comfort in the fact that everything I was feeling, I was feeling with him. Hearing a man tackle his sexuality in such a sensitive way while I was growing up was a blessing.

Whenever men are the subject of fantasy on the album, Frank is never overly sexual in his detail, as queerness is often presented as being. To clarify, it is his prerogative to be as sexual as he pleases, but when I was younger, I related to the way that he bares his soul when writing about other men, whether his life was being ruined by them in Bad Religion or he couldn’t stop thinking about how buff they are in Forrest Gump.

There was a painful normality to the way that he fell in love. When addressing other men on Channel Orange, and even when alluding to bisexuality in post-Channel Orange singles, Frank’s sexuality belongs to him – he never feels any pressure to explain it further. I learned this from him.

Frank helped me to normalise being gay as a teenager, and I care deeply about his perspective. Everything that he does is interesting to me. He is in my university projects, in the design of my apartment, in the words on my grey hoodie, and in the way I see life, the rest of which will be lived with Channel Orange playing softly in the background (just as it was when I was growing up).

I would have ended up a very different man if I hadn’t purchased that album by accident when I was 11, thinking that it was a 50s reboot and not a new R&B album that would change me forever. Thankfully, I did.

Samuel is an ambassador with Just Like Us, the LGBT+ young people’s charity. If you’d like to volunteer to speak in schools on their Ambassador Programme, sign up now.