The Stonewall co-founder, EastEnders star and former MEP spoke to GAY TIMES ahead of the release of his new book One of Them: From Albert Square to Parliament Square.

It’s been a hectic time for Michael Cashman over the last few months. Working in the House of Lords in the run up to the Brexit deadline, while trying to squeeze in promotional opportunities for his book – he hasn’t had much time to himself. “It’s a fish and chips existence at the moment,” he explains. “You go home and get a bag of fish and chips and then you wake up with them. I mean there are worse things to wake up with. Like a person.”

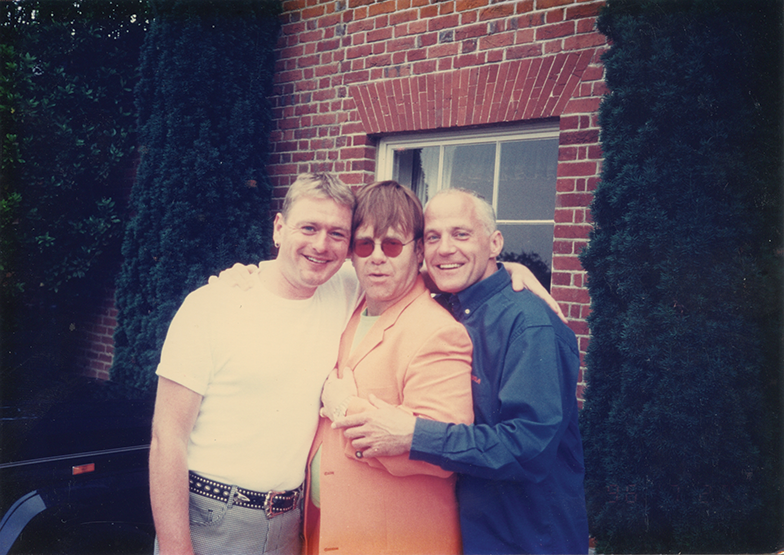

Over a leisurely coffee in Soho’s L’Escargot club, Lord Cashman talked us through many of the highlights and challenges from a life full of LBGTQ+ rights activism. From growing up in the east end in the 1950s, to experiences of gay life in the 1960s, through significant moments including the founding of Stonewall, the introduction of Section 28 into law and the HIV/AIDS crisis, he offers a fascinating first-hand account of experiences almost unimaginable today.

While in the UK many equal rights have been won – in the eyes of the law, even if there’s some way to go before that becomes the lived experience of all members of the LGBTQ+ community – Michael’s experience growing up as a gay man was very different. He talked us through his childhood experiences in the 1950s and 1960s – some of which does not make for easy reading.

“We lived a difficult life in the east of London right in the heart of the docks – back then it was a different world, there were ships arriving from all around the world, there was chaos, there was a community. Old Mr Pittaway who banged away on his piano upstairs and Betty Wood whose husband was a long-distance lorry driver, she was always good for a shilling for the gas meter when we ran out. There I was in this community, all the time aware that I was different.

“From the age of seven I knew I was different. Something happened to me where a young docker asked me to help him, offered me a shilling. He ended up sexually abusing me, and I knew I couldn’t tell anyone, I had to bury it. Because when that kind of thing happens to you at that age you can’t find the words, and if you could find the words you believe that you will be blamed for the trouble, if people even believe you. I think the way I buried it was by becoming this little extrovert.

“Suddenly at school I belonged when the teacher asked me to read to a class and I captivated them. It was the most amazing experience, I think that’s where I found my love of acting, of wanting to go into show business. For a young kid in the east end there were three ways of escaping; you became a footballer, you went into show business or you became a criminal. I knew I wouldn’t be any good as a criminal and I knew I would be appalling as a footballer so I chose show business.

Michael had his first big break shortly after leaving primary school. “Mother luck intervened at my secondary modern at the age of 11 and I ended up auditioning for Oliver in the West End and going in at the age of 12 playing one of Fagin’s gang, then ultimately playing Oliver and it changed my life. It was decided that I had to leave my secondary modern school which was a relief!

“It was decided that I would go off to stage school in Surbiton. That was decided by my then-manager so that he could begin grooming me into an abusive relationship that went on for a number of years. It’s extremely important to be honest and to deal with the dark and the light otherwise there is no contrast. You have to own everything that’s been done to you, and that you’ve done. Otherwise you have no control and it owns you.

“Although I had this amazing career as a young man, starring in television dramas at the age of 13, appearing with Billy Fury, being in plays with Alastair Sim and big stars of the day, there was also a dark undercurrent within my life about what was happening to me, and an absence of awareness by my parents.

“Then discovering gay life when I was 15 years old, I went on a tour with Peter Pan and I discovered gay Britain. The older gay men in the cast kept telling me we were criminals and I should not be flaunting myself. This was 1966 – I was breaking the law by even trying to look for a man, let alone pick one up, which was called procuring for an immoral purpose, for which you could be and were arrested.

“You were made aware of your criminality by being attracted to other men, by a lot of older gay men, and by the newspapers that reported the transgressions of vicars, and gay men in the darker columns of the News of the World. And that has an amazing psychological impact on you for the rest of your life, if you’re not careful.

“Having said that, when I came back to London and discovered the gay life of Soho that was so different from Blackpool and Hull and the other places where you were in a backroom bar… knowing that you belonged with other people was heart-warming. In London the first gay club that this friend of mine took me to, young men my age dancing cheek to cheek in a disco, I walked in and I thought ‘I know this is it, I’m in paradise!’

“It was a world that existed an hour away on the bus, but it was another planet and what happened there had to stay there. People lived in fear of somebody just casually coming in from the street and seeing them surrounded by other men in what was clearly a gay bar. There was always the fear that some people had of exposure. But for a young gay man like me it was joyous.”

While this was evidently a difficult time for many members of the LGBTQ+ community, we wondered whether there might be any nostalgia for a counterculture, an underground scene. Is there anything Michael misses from those days? “Nothing. There is nothing good about having to live a secret, or creating a dark area and pretending to be somebody else, so that you can own a space in the world. People create their own underground culture in certain clubs – the fetish bars, the saunas.

“The fact that two people of the same sex can get married, can defend their place in society, that makes society better. It creates stable relationships. People who feel they belong give off their best. And so… go back to that other age? Absolutely not. I’ve always said it’s better to be able to opt out of equality than to be refused the option of opting in.”

Many people will know Michael from his time in EastEnders, including a gay kiss on British television screens which caused outrage in 1987. “The whole time in EastEnders is a pivotal part of my life. They outlined the character, outlined the story. Then they said, ‘we’re trying to cast a straight actor’. My ears pricked up and I said ‘why?’ and they said, ‘because he’s gay’. I immediately understood because a straight actor wouldn’t have to fend off the tabloids from their private life.

“I also knew that they were introducing this into the show at a time when AIDS and HIV was depicted by the right wing as the gay plague. People were told you could catch AIDS by sitting next to a gay man or using a beer mug that hadn’t been properly washed. All those factors, and going into that show, meant that the reaction of the tabloids was electric.

“The right-wing politicians went mad, called for the show to be taken off air, why were they putting a homosexual this programme family programme… before I joined the show, The Sun announced my arrival with the front-page headline ‘EastBenders’. After a while they outed Paul to his family and his friends in the News of the World. Once he had been outed he was no longer newsworthy, they didn’t want to portray us as a couple, they were only interested in a gay couple if there was scandal.

“An interesting footnote to all of this, the second kiss happened in 1989, that was a full on, mouth-on-mouth kiss. But because we’d done the first one, the reaction to the second was hardly noticeable apart from the Piers Morgan piece in The Sun. That was about ‘yuppie poofs’ and depicting a kiss as a sex scene, which was stretching facts to the end of fantasy.

“That first kiss, Gary and I had no idea the reaction that it would cause. I remember there was a letter from a woman saying her nine-year-old asked her why Colin was kissing Barry. And she said, as mummy loves daddy, so Colin loves Barry. When I read that letter, I understood why the tabloids and the right-wingers were outraged. We were challenging their narrow view of the world and they didn’t like it.”

Michael has had to put up with an awful lot over the years – do the long-term benefits outweigh difficulties? “Absolutely. I’m so proud of what the BBC did, the fact that we depicted this relationship in an ordinary way, whereas it had always been extraordinary. Helping to change public perceptions is absolutely worth it. We helped to break down stereotypes. Thereafter other kisses followed, it wasn’t controversial, it was a proud period for the BBC.

“I did have bricks through the window as a result of the News of the World article which gave our address. To see your photograph on the front of the newspaper like me and Gary did, with the banner headline ‘Filth: Get This Off Our TV’… when I look back at the reportage, it was nasty, it was vicious, and in the middle of that – which is why it was so pivotal – the Thatcher government introduced the first anti-LGBTQ law in a hundred years.”

Michael explains that campaigning against Section 28 would become a huge part of his journey. “I remember at the Manchester Free Trade Hall, the stars that were there, academia, artists, writers, professors, they came out against Section 28 because they saw the inherent danger in censorship.

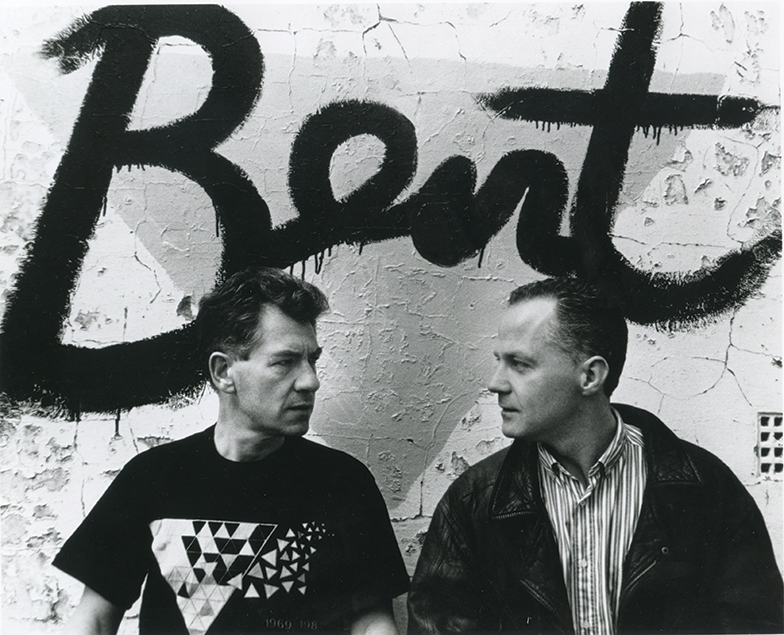

“When we lost that battle, I said to Ian McKellen one Sunday morning we’ve got to form a lobbying organisation, so another Section 28 doesn’t happen again. We set in train the beginning of Stonewall and the following week he said ‘come down, somebody else has got the same idea!’ and we sat on the banks of the Thames where his house is and we formed Stonewall.

“I remember the media portraying us as predatory paedophiles, portraying two books, Jenny Lives With Eric and Martin and The Milkman’s On His Way, as books that were given to children as young as seven or eight and the tabloid press were running this, largely fuelled by the Daily Mail. It was complete bullshit, these two books were teaching aids for teachers in case they had young pupils who were in similar situations and had questions. The truth did not prevail, the myth did.

“When Ian and I – and Lisa Power and Duncan Campbell and Jennie Wilson – started to set up Stonewall, we set it up with a remit. We got attacked by lesbian and gay activists and media as to who did we think we were. We got on with it because if you can’t live equally to others you can never be yourself. You’re always tolerated – tolerance does no one any good. We lost the battle against Section 28 and so we were determined we would win the war of equality.”

As well as being at the centre of the furore surrounding British TV’s first gay kiss, and actively campaigning against Section 28, Michael experienced some heart-breaking moments at the height of the HIV/AIDS crisis. “We lived through that period where we saw almost a generation wiped out by AIDS and HIV, people dying and in their death were stigmatised, were alienated. Some of them – most of them – died brilliant deaths with great integrity and surrounded by love.

“I’d go off and I’d visit a hospice, they wouldn’t say who was coming, they would ‘say we’ve got a celebrity, would you like a visit?’ I walked into one of the rooms and there in the bed was a friend of mine. That was when I learned that he had an HIV-related illness, and I had to swear to him that I wouldn’t tell anyone, such was his fear that he couldn’t tell his friends. Ashley died about six weeks later and was taken home and buried by his father.

“An ordinary boy who died an extraordinary death, that really brought it home about the alienation of the reportage around gay lives, and gay lives that were associated with HIV. It’s those moments of heroism I remember – Ashley, the boy with an HIV-related illness. And that march in Manchester at the Free Trade Hall.”

Even though a lot has been done to amend laws, work towards equality and change public perception towards members of the LGBTQ+ community there’s still a way to go. “There was a huge battle around inclusive relationship education at Anderton Park School, the headteacher sought an injunction and got the local authority on side. We must never forget that the QC against the permanent injunction was joined by the Christian right.

“Our enemies never go away, they’re better financed, they’re more adept at the way they approach. I heard ‘LGBTQ’ used in a similar way to 32 years ago and Section 28 that somehow we were a threat to young children. They said to the teacher, why did you spend money on bringing those books into the school? We have to remain vigilant – our rights are never taken away directly head on, there’s always an excuse used.”

We asked him about the LGB Alliance, and while he wouldn’t be drawn on them directly, he had some choice words about groups which don’t seek to support the rights of others. “How can you claim to be an alliance if you’re deliberately excluding people? As soon as you surrender one minority’s rights, you begin to feed the tiger and the tiger is always hungry, it will eat the next group’s rights.”

Michael has lived an extraordinary life, and is sharing his story in his new book. Considering his experiences and achievements, we wondered what might be next for him? “Post-Brexit, we make sure that the rights contained within the fundamental charter of rights are affirmed elsewhere, and that there is no creep using the excuse of ‘oh it’s the economy’ or ‘we need to free up employers’ so that they can decide who they give those services to, not the government.

“I want to defend the rights we have. I think they will come under attack, there is a growing intolerance. I want to build on those rights, I want to help to extend them into other countries. Brexit I’m afraid has shown that there’s a dark underbelly in British life. Xenophobia, racism, increasing homophobia, antisemitism, misogyny, transphobia, biphobia, all of those things have been given a license.

“The license is being increased by politicians pandering to populism rather than leading public opinion to a different place. That is the nature of politics, the courage to be unpopular in the short term to do what’s right in the long term. At the moment, everything is about short term, everything is about tonight’s news, tomorrow’s headline, and it will not serve us well.”

Michael Cashman’s new book One of Them: From Albert Square to Parliament Square is out now.