As trans people are continually pushed out of the public realm, the safety of our private spaces becomes even more important. As we struggle against a hostile external world, our domestic realms become places of safety, actualisation and normalcy. Outside the antagonistic restrictions of the public realm, we are able to craft places that accommodate our bodies, needs and sensibilities. So how exactly do we create our notions of family, home and the mundane?

These are the questions S K Godfrey and Marf Summers ask in ‘Burn the Sheets’, at House of Annetta, the spatial justice organisation based in Spitalfields, London. The exhibition occupies the ground floor of the grand dilapidated Spitalfields townhouse and brings together eight trans artists from the UK and beyond, including Roddy Loewe, Pear Nuallak, Lou Lou Sainsbury, Rose Schmits and Chole Swords & Jory Cherry. The artists’ works have certainly come to feel at home, with traces of their bodies felt across the two rooms: Summers’ embroidered underwear drapes off door handles, Sainsbury’s hormones are muddled in an open cabinet drawer, Swords & Cherry’s used toothbrushes hang from the ceiling and Schmits’ chamber pot — wryly labelled ‘Emergency Trans Toilet’ — sits pretty on the window sill ready for use. Lest we forget: a safe space for trans people must, first and foremost, accommodate our bodies.

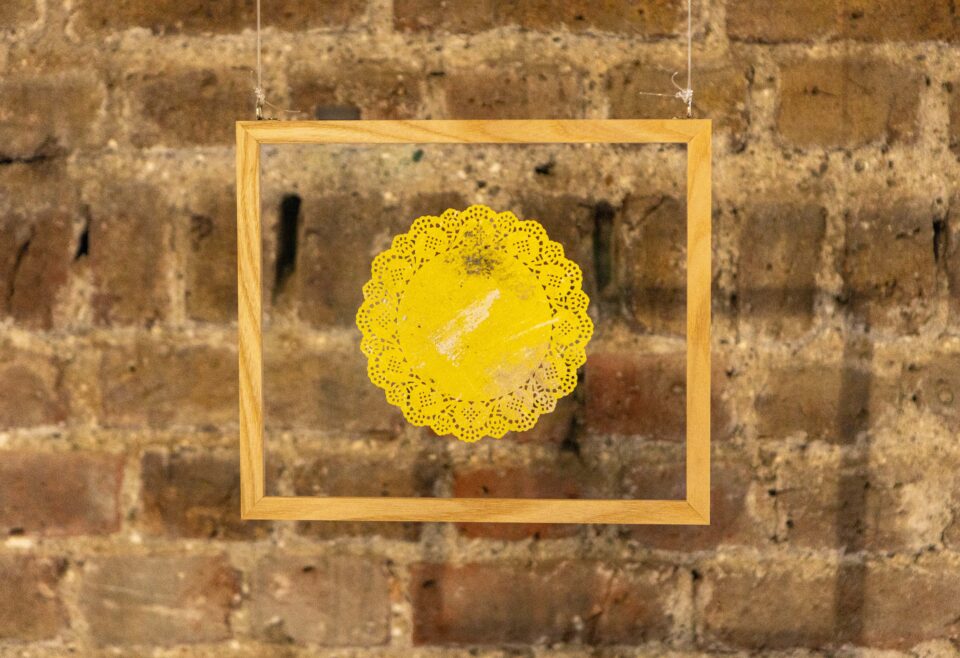

Craft practices – such as knitting, pottery and crochet – have historically been where the body and the domestic come together, as craftspeople and artisans have handmade objects often in service of the home and quotidian life. No wonder, then, that craft techniques are found throughout the exhibition, with works considering how objects handmade by trans bodies have their own sensibilities. Take Summers’ ‘Bread Doilies’, framed doilies delicately hand-cut from sand paper, which produce a material tension between rough industrial tools and soft home comforts, playfully yoking stereotypes of ‘masculine’ hard labour and ‘feminine’ domestic labour.

Elsewhere, S K Godfrey’s installation uses smocking – a type of embroidery that gathers fabric in unusual patterns – to create a mysterious atrium in the corner of a room. Made from hand-dyed netted curtains and hung from bent copper rails, the hanging fabric creates a room within a room. Peep inside and you see more painstaking craft as three cerulean glass plates are set on a carpet of delicately beaded trim. The work invites us to imagine the bodies for whom these places are set, and for what occasion they are gathering. Much goes unanswered, and you wonder whose personal world this is, what is happening, and whether or not you are a welcome guest. Like much of the traditional arts and crafts referenced in this show, Godfrey’s work juxtaposes time: smocked curtains evoke grand Victoriana, coloured glass plates come straight out of a 70s dinner party and the shape and recurring blue feel oddly futuristic and alien. This discordance of time alongside the question of being welcome speaks to the awkward sense of place trans people feel in this contemporary moment.

The Dutch-born Rose Schmits explores similar themes in a series of tongue-in-cheek porcelain, inspired by her home region of Delft which is famous for its blue and white crockery. In each instance, the politics of public life inevitably seeps into the private domestic realm. The pots are each painted with slogans, memes and visual puns, and are designed to have some practical bearing to trans daily living – one pot is painted with “The Notorious HRT”, inviting an imagined use as a hormone container whilst also noting the fear-mongering around transitioning. Elsewhere, a chamber pot labeled “Emergency Trans Toilet” is a droll critique of bathroom legislation, bringing to mind similarly draconian attitudes of the Victorians and the restricted public access trans people experience. Another pot is painted with “Trans people have always existed and always will” in frilly cursive – something of the t-girl’s “Live, Laugh, Love”, posing a ‘trans kitsch’ perhaps. In Schmit’s work, we might see a hopeful reimagining of the past through the use of traditional craft.

Pear Nuallak’s installation takes a less romanticised view of traditional domestic decor. Titled ‘Anti-Chinoiserie’, Nuallak darns an old wall-hanging patterned with orientalising imagery of East Asian ceramics and rural labourers. Nuallak threads their own narratives, overlaying fabric depicting European fruit farmers, hand-darned with legs akimbo and spirits added by the artist. This layering of fabric asks us to think about whose image is used for decoration in our homes. Beneath, the wall-hang is knitted bog landscape, with yarn dyed with pigments derived from plants foraged from the artist’s home area of Croydon. Here we’re invited to consider how the divisions of inside and outside blur in our own personal sensibilities of home, and how handcraft can contribute to acts of world-building.

Rody Loewe’s painting of an eight-limbed figure, hung above a disused fireplace in House of Annetta, functions as the patriarch’s grand portrait. Except in this exhibition’s imaging of the home, this figure is not an old white lord, but a West-African shapeshifting trickster spirit called ‘Anansi’. The character, who derives from Akan folklore, is often depicted as a spider and is known for its story-telling skills. Hung above the fireplace, the painting makes me think about how we can weave new stories amongst ourselves to create new traditions together, an act we might find agency within the home.

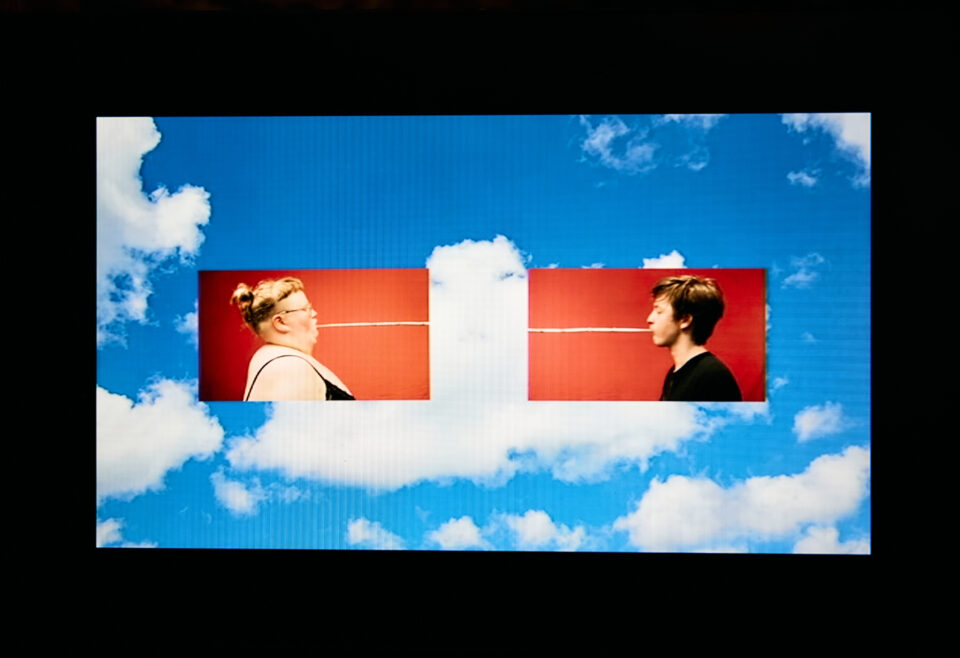

The two video works in the show give a sense of forging new normals and traditions, and note a trans desire for the safety of norms. Take Lou Lou Sainsbury’s video ‘a fantastic body’, an otherwise surreal film, where Sainsbury cuts and stuffs a home-made doll with bones, peach pits and hormone pills, before stitching it back together. Despite this strange and at times unsettling ritual, the video returns to the image of Sainsbury attempting to breast-feed the doll in her kitchen – a trope of the maternal domestic. Rather than a wry subversion, Sainsbury’s breastfeeding is more a peculiar attempt at a norm, one she can never quite attain without baggage. Elsewhere, Chole Swords & Jory Cherry have hung a series of double-ended toothbrushes from the ceiling. An accompanying video demonstrates the tools in action, as Sword & Cherry playfully attempt to simultaneously brush their teeth, neither being able to do so without the help and attention of the other. A personal daily ritual made social, the video speaks to a necessary mutual dependency often found within trans living. Their second video sees both artists clamber under sheets together. Hidden under the fabrics, their veiled bodies together resemble a mound or a hill within a landscape. This is perhaps a yearning for naturalisation, physical togetherness and place.

The curators call for us to “burn the sheets and wrap yourself, reborn, in fresh ones.” If this exhibition seeks anything, it is the agency to desire the safety of a new normalcy. Whilst ideal imaginations of political ‘queerness’ may seek to disrupt, subvert and challenge norms, Godfrey and Summers ask: what if we want the safety of a normal forged anew and designed by us?