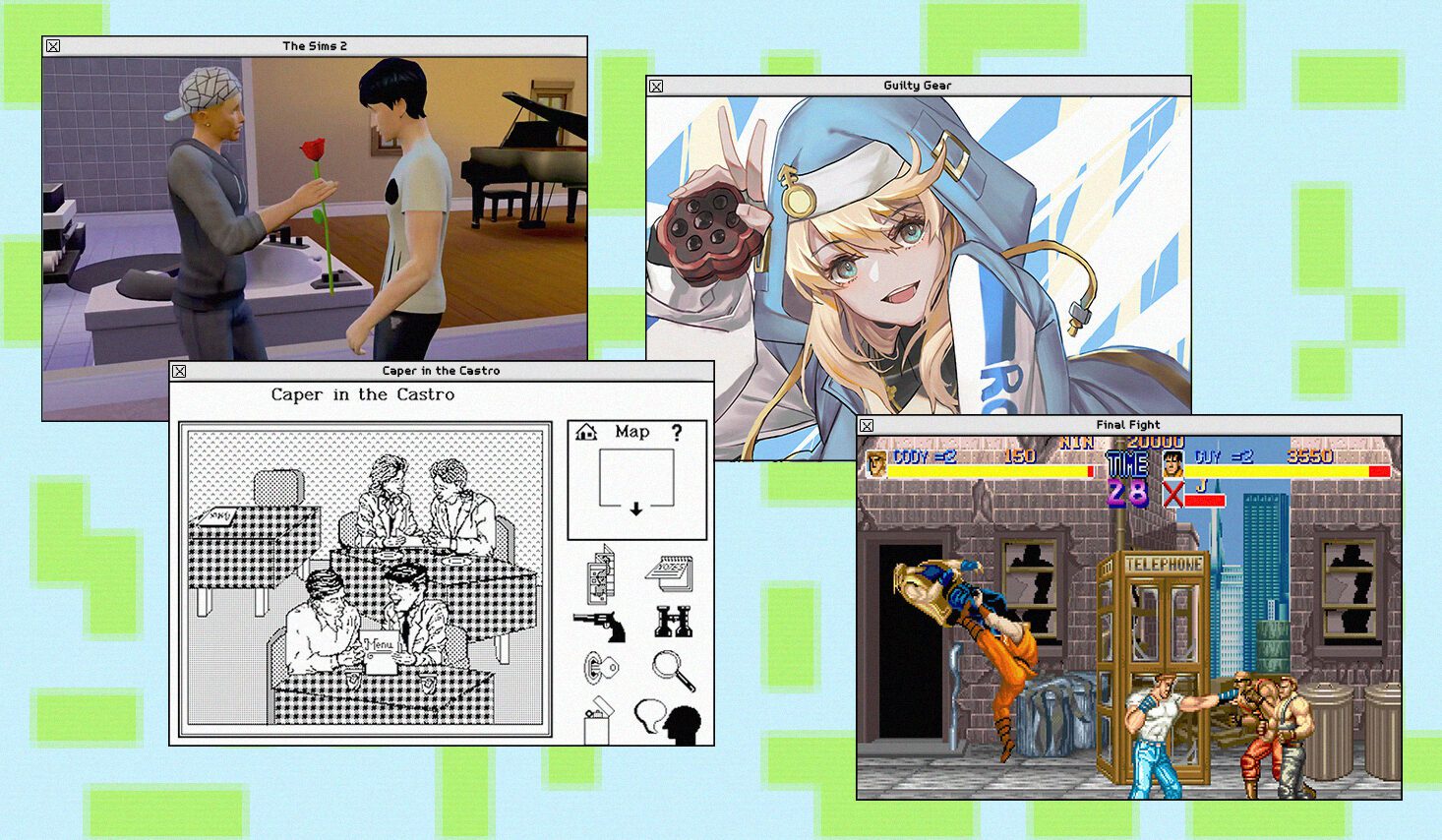

In 1990, Capcom was in talks to port its Super Famicom game Final Fight – a beat-‘em-up side-scroller adapted from a planned Street Fighter game – to Nintendo’s Super Nintendo Entertainment System. Nintendo heavily censored the port, including objecting to female enemies Roxy and Poison, on the grounds that it had a policy against depicting violence against women; the Japanese developers responded that Roxy and Poison were either ‘transvestites’ or trans women, and would therefore not cause controversy by being attacked. Nintendo was unsatisfied by this, and replaced Roxy and Poison with male enemies called Billy and Sid for the English SNES port, as well as renaming a boss called ‘Sodom’ to ‘Katana’.

The Final Fight saga is representative of a lot of gaming history: queerness and transness often peek from under the surface of video games, buried and/or corrupted by censorship and pejorative assumptions, but visible if you dig a little. The hidden gay and trans history of game development is rich, and important to connect with, given the false assumption that gayness and transness are new, ‘woke’ invasions into traditional gaming. But it’s also a complicated and difficult history, full of frustrations that temper the joy of finding hidden queer figures: Roxy and Poison are aesthetically cool characters who are fun to fight, for instance, but they’re symptomatic of how trans women are considered more culturally acceptable to injure than cis women. Gaming is sometimes thought to be in such an embryonic stage for queer and trans people that we’re expected to be grateful for any representation we’re given, rather than interrogating the nature and context of that representation. But gayness in games didn’t just show up in the 2010s. It was always there, or it was kept out.

Nintendo and Sega’s censorship codes heavily limited allusions to homosexuality or being transgender through the 80s, 90s and 2000s, under the label of blocking “sexually suggestive or explicit content”. The pattern of Roxy and Poison has repeated multiple times under these censorship codes, where a character whose gender is inconsistently understood in a Japanese game – she may sometimes be referred to as a trans woman, and sometimes as a ‘crossdresser/transvestite’ – has her transness erased, both by players and by the American ports. One famous example is Bridget in the Guilty Gear series, who was eventually confirmed as a trans woman in 2021’s Guilty Gear Strive. But they appear in games for children as well: Vivian, a main character in the recently remastered Paper Mario: The Thousand Year Door, is a trans woman in every release except the English-language one, while Super Mario 2 character Birdo was originally described in the 1988 manual as someone “who thinks he is a girl” and who would rather be called Birdetta. (Nintendo’s response to questions about Birdo has essentially been to filibuster for 35 years, changing pronouns or referring to her as “of indeterminate gender”; the British English version of 2018’s Super Mario Party refers to Birdo with male pronouns.)

There are better representations of queerness during gaming’s early period. A few explicitly gay video games from the early era survive, most famously C. M. Ralph’s 1989 point-and-click adventure Caper in the Castro (where lesbian private detective Tracker McDyke must save her drag queen friend Tessy LaFemme), while 1998’s Fallout 2 and 2004’s The Sims 2 were two of the first games to allow gay relationships and gay marriage. Will Wright actually dedicated the original Sims to the memory of Danielle Bunten Berry, a brilliant trans woman game developer who developed the 1983 multiplayer game M.U.L.E., a game regularly cited as one of the most important and influential early computer games. Berry is a bittersweet figure in gaming history, a trans woman who had an immense effect on the industry but was shunned by it when she transitioned; Brian Moriarty, the creator of Loom, recalls being approached by developers in the mid-90s who wanted to found a game company, and asking them “Why aren’t you talking to Dani Bunten?”: “I mean, Dani Bunten is the world’s foremost authority on multiplayer games and they just looked at me and…I knew why.”

A lot of the archive of queer game development is lost, as people died or left the industry – Berry herself died of lung cancer in 1998 – but an important testament comes from Tim Cain, the creator of Fallout, who has worked in the game industry since the 80s. Cain talks in a YouTube video about 42 years being a gay man in the industry, 20 of which he spent closeted at work: “I’ve never met anyone gay in the industry older than me.” He describes a pervasive atmosphere of homophobia at some of the studios he worked at, particularly Interplay (where he made Fallout), and of transphobia towards a trans woman colleague in the ‘90s; he also describes getting pushback from Atari about content in 2003’s The Temple of Elemental Evil, including having to cut a lesbian character. (Another gay character, the flirtatious pirate Bertram, stayed in the game.) He does describe a relatively positive experience coming out in the mid-2000s, however, with the president of his studio telling him “if you have any problems with homophobia, call me, we don’t put up with that”.

By the late 2000s, queer gamers and developers seemed to be conscious of being at an in-between point, where the desire for major queer and trans releases was significant enough to be recognised, but still felt a little way off from being feasible. A fascinating time capsule can be found in gaming magazine The Escapist’s 2009 issue, ‘Queer Eye for the Gamer Guy’. You can still read its guest editor note from Flynn Demarco, editor-in-chief at the now-defunct GayGamer.net, which paints a vivid picture of the queer gaming landscape in the late 2000s: “Until very recently, homosexuals in games were mostly treated as limp-wristed sissies, jokes on the player or sometimes, as in the case of lesbians Hana Vachel and Rain Qin in Fear Effect 2, an enticement for the horny teenage boys game companies assume make up their audience.” Demarco also notes the lack of trans characters, and that “with the exception of Bridget [from Guilty Gear], trans and cross-dressing [sic] characters [are] always represented as some kind of enemy to be vanquished.” He praises Bully, Fable II and The Ballad of Gay Tony for better, non-stereotypical gay representation, but says that he doesn’t expect to see “a game with a gay central character” anytime soon.

Queer game development has proliferated through the 2010s and 2020s, particularly with the launch of indie platforms like itch.io and Bitsy; we also now have a handful of AAA releases with “gay central characters”, and one with a trans protagonist (Tell Me Why). Tim Cain is openly positive about the future of queer game development, and has said: “I know a lot of LGBTQIA+ people in the industry, they’re well-received in their teams, they bring a lot of interesting experiences, we get a lot more interesting characters in games – everything’s better.”

But it’s also a fragile time to be a queer developer, player or critic, given the continued marginalisation of queer and trans people in gaming culture and the long shadow cast by GamerGate, the devotedly misogynistic, homophobic and transphobic harassment campaign that defined mid-2010s game culture. The cultural treatment of 2023’s Hogwarts Legacy has reflected our precarious position: a few outlets acknowledged the ethical issues with supporting a game that directly funds an anti-trans activist, Wired got substantial right-wing backlash for its negative review of the game, most outlets didn’t comment or commented in studiously neutral terms about the ‘culture war’, the game continues to be massively popular, and the entire media circus implicitly dismissed trans people and their oppression as irrelevant: something far-off, to debate or mull over or feel a twinge of guilt about, but not real people worth sticking your neck out for.

But Danielle Bunten Berry, Emilia Schatz, Lena Raine, Rebecca Heineman, Jennell Jaquays, other trans woman creators and developers and artists who aren’t public for fear of reprisal – they stuck their necks out. Their fingerprints are everywhere in modern gaming. Gay and trans fingerprints are everywhere in modern gaming, full stop. The fiction that we are far away from the centre of gaming is one through which gaming sustains its apolitical veneer and profit margins, but it’s a thin fiction, easily pulled apart.

The future does look positive for queer game development, and for the art that will be made and enjoyed in the coming years. But to understand where we’ve got to – and the problems with representation as it exists – we have to stay in contact with the murky, fascinating, and at times very upsetting history of queerness and transness in gaming: the effeminate villains and censored content, the developers who were pushed out of a quietly hostile scene, the erasure and fetishisation of trans people, and the ways in which queer content in games is still often built to be conspicuously avoidable. Only then can we push past the placid face of big gaming companies, and excavate their continuing complicity in a violent history of queer suppression.