Celeste is one of the most critically acclaimed and beloved platformers of the past decade; players are still making discoveries and accomplishing incredible feats in the game six years after its release. (A recent favourite? EuniverseCat’s minimum-grabs speedrun, which took three weeks). But it’s not an ostensibly very trans game. It’s mostly about a woman climbing a mountain. There’s a short cutscene where the protagonist has a miniature trans flag on her desk, but you only see that if you complete the Farewell DLC, which is a very tricky, long DLC that less than 20 per cent of players finish. And it’s only a little flag, anyway.

So why is this game so iconic to queer and trans gamers? Celeste is an influential trans game despite not being ‘explicitly’ trans – and the reasons why go against a lot of prevailing wisdom about what makes a game queer.

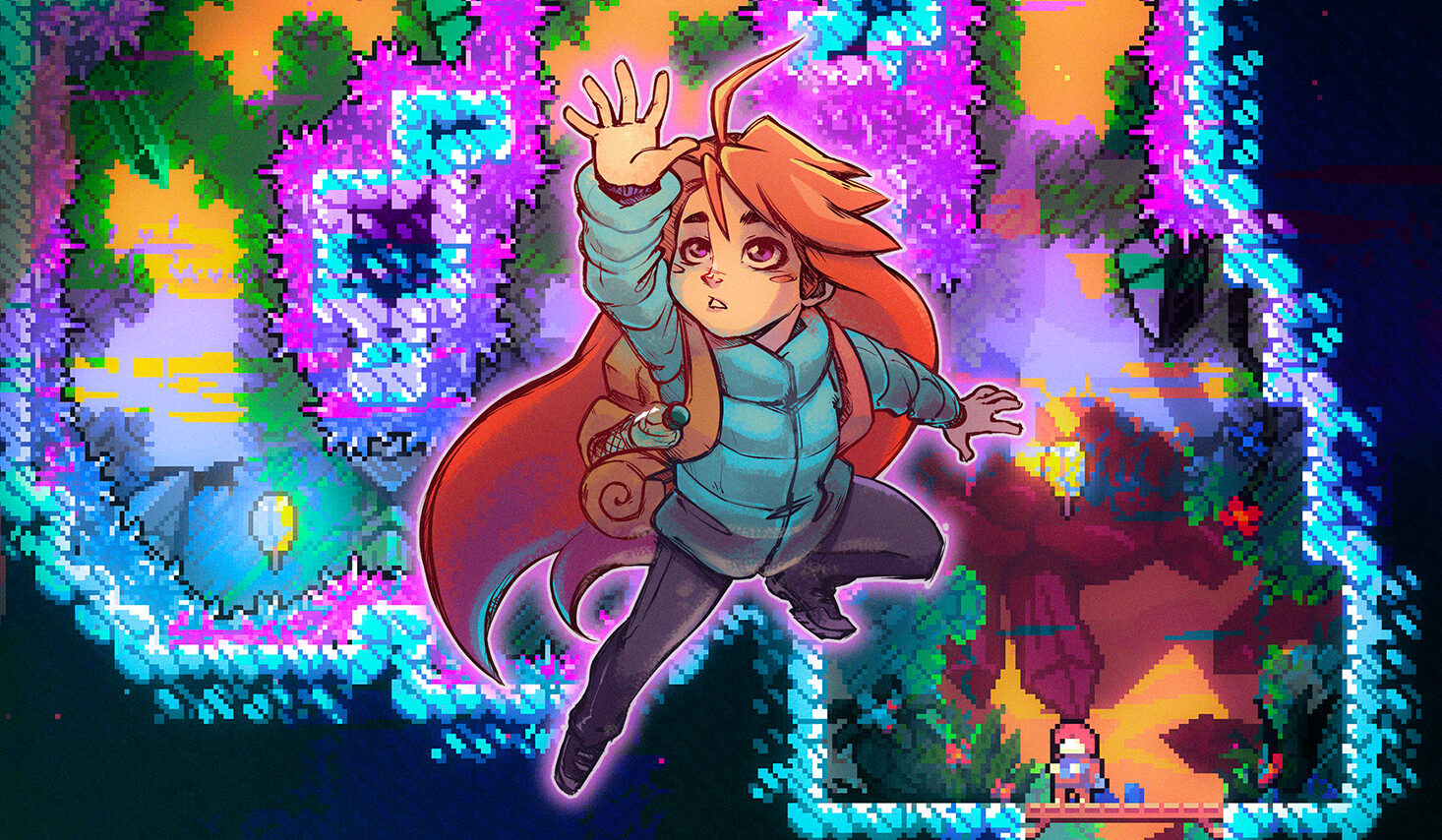

In Celeste, you play as Madeline, a young woman with pink hair who seeks to summit Celeste Mountain (a fictionalised version of a real mountain in British Columbia). You move through each room through jumping, dashing and scaling walls, and restart the room if you fall. Motion in Celeste feels good, fluid and intuitive; at times, deep in the game, you can feel like you’re flying. The climb is a ‘real’ climb in the world of the game, but the game phases between dream and reality with little signal of where you are at any given time: inner demons manifest as tangible monsters, a spirit stalls a cable car, a hotel is run by a ghost.

https://www.gaytimes.co.uk/originals/best-lgbt-video-games-2023/

Accordingly, it’s not really a game about athleticism – ‘real’ climbing. Rather, the rooms in Celeste represent psychological challenges and snarls of thought (sometimes visible, tentacular snarls) that must be handled and moved through physically. This has particular resonance for trans people: our physical grappling with gender and living – how do I want to be perceived? What am I? What does this transformation mean? What will it do? – is played out through strange tests of embodiment: presentation, movement, gesture, speech, even posture. Accordingly, representing that bodily fluidity and mind-body relationship requires a balance between realistic movement – physical exhaustion mechanics, for instance – and dreamlike movement.

The game fluctuates between that zen game state of moving through the rooms, and the narrative cutscenes, where we get a sense of Madeline as a character: determined, cynical about other characters’ mentions of hauntings and people ‘seeing things’ on the mountain (“You should seek help, lady”), low on self-esteem. Later, talking to her new friend Theo, she reveals a dimension of intense anger and frustration with herself, where she feels like she can’t move past “stupid THINGS that happened forever ago…I should be over them. None of it matters.”

There are subtle cues that reward people looking at Madeline’s portrayal through a trans lens

Her issues feel overwhelming, yet intangible; all-consuming, yet supposedly trivial. She has depression and panic attacks, and a wealth of things left out of that simple description. She’s “barely holding it together.” It’s a portrayal that’s relatable to anyone who’s struggled with mental illness, but there are subtle cues that reward people looking through a trans lens: Madeline protests that she’s “just not…photogenic” when Theo wants to take a picture of her; she’s battling a distorted version of herself in the mirror.

But why use this lens in the first place? Well, Madeline isn’t confirmed as trans in the game, though the scene at the end of Farewell deliberately includes a few elements intended to imply her transness (the flags, a bottle of pills, a photograph where Madeline’s hair is shorter). But the game’s director and writer, Maddy Thorson, confirmed that Madeline was trans in a blog post, and that Celeste’s composition was entangled in a long process of her realising her own gender: “During Celeste’s development, I did not know that Madeline or myself were trans. During the Farewell DLC’s development, I began to form a hunch. Post-development, I now know that we both are.”

So, Celeste, without the developer explicitly intending it, captured preconscious transness. This is part of what makes it so beloved and thought-provoking in trans communities: it authentically renders the experience of transness before it is understood as such. It gets at the feeling without naming it, which means that it can slip the bonds of how overwhelming, even cloying, transness can sometimes feel when it is first named – the initial deluge of stereotypes, assumptions, questions, fears, all coated in baby blue and baby pink and white.

It feels real, and the reasons it doesn’t name transness feel connected to early transness, rather than being a byproduct of cowardice or a drive for profit. Early transness and pre-transness is often full of the things Madeline struggles with: incomprehension, fear, anger, self-hatred, feeling trapped and driven to dangerous experiences that promise transformation, or else to “drinking and arguing with people on the internet”, as Madeline says when asked how she responds to her problems.

Yet, also, even as it embodies an authentic element of trans experience, Celeste’s journey is an incredibly archetypal hero’s journey. To risk a very obvious spoiler, Madeline climbs a mountain (albeit nonlinearly), and experiences personal growth in the process. She has a complex story, but it’s not in a complex form. In using a ‘universal’ type of story structure to tell a trans story, Celeste presents Madeline’s life as available for understanding and empathy, and connected to basic forms of human struggle and change. As Thorson herself puts it: “if you’re a cis person and you personally relate to Madeline […] you could take this as evidence that trans and cis feelings aren’t so different, that the chasm between transness and cisness isn’t such a wide gulf, and that most of the ways that trans existence is alien to you are the result of unjust social othering and oppression.”

https://www.gaytimes.co.uk/culture/best-lgbt-video-games/

In Kotaku’s “How the Celeste Speedrunning Community Became Queer As Hell”, Jeremy Signor talks to queer speedrunners, modders and fans of Celeste about their relationship to the game; nonbinary speedrunner frozenflygone attributes their discovery of their gender to “reflection on this game” and feeling “empowered by” the queer community around it, while trans speedrunner Blobbity21 speaks about how its treatment of mental health resonates with her struggle with “actually confronting your inner demons and getting stronger by moving past them instead of just running away from them”.

The multiple possible interpretations of Badeline, Madeline’s doppelganger, in the game can further the game’s resonances through and beyond transness: does Badeline represent Madeline’s pre-transition self, full of anxiety and anger, who Madeline thinks she can sever from her? Does Badeline’s focus on averting risky, scary experiences mean that Madeline is stalling on aspects of her transition out of fear? Does her transness mean she believes she is undeserving of, or incapable of overcoming, her other issues?

Celeste is a trans game in a way we have little access to, in a landscape and marketplace that demands tags, labels, explicitness

None of these are the canonical interpretation of the game; they’re all swirling in the field of abstraction around its art and story, available as methods of reading. Celeste is a trans game in a way we have little access to, in a landscape and marketplace that demands tags, labels, explicitness. Every year we get lists of ‘queer games’ coming out the next year, and it’s very difficult to determine what ‘queer game’ actually means, particularly prior to release. Does a minor character have a throwaway line? Are there central queer themes? A question none of these get at: is it good? Substantive? Meaningful?

Celeste is a separate story to Maddy Thorson’s story – the game shouldn’t be simplistically projected onto her journey – but her testimonial about the game’s relationship to her own transness reveals a half-hidden kind of trans and queer art: art that is full of queerness and transness, that embody and shape that experience, but that doesn’t name it or precedes naming it. This is commonly talked about in literature, television, film. But games, we seem to think, are more explicit, more upfront. They are focused, first and foremost, with ‘representation.’

Explicitness isn’t the problem. God knows we’ve had enough coy, market-friendly hinting. But there’s a level of interpretation that gets left out of the ‘representation’ paradigm, the ‘guy on Steam Communities asking you if this game is woke or not’ paradigm. The mechanics and stylistic choices of a game, its flow, its directionality, its vocabulary of images, are as or more crucial to why a game is queer – its sticking power with queer people – as its definitive queer statements. Celeste’s movement and form ends up shaping itself around transness, chasing it through both reality and fantasy. It is loved by many of us because it is of us. It reminds us how we get here.